Thanks for visiting! This is the Austen Connection newsletter and podcast. If you are not signed up yet you can take a few seconds to sign up for free, or support at any level - below - and get all of the conversations dropped right into your inbox. Join us!

Hello friends,

We’re dropping in to your day with a brand new Austen Connection podcast episode - and this one is with a wonderful friend and colleague who sat for an in-studio conversation that was illuminating, eye-opening, and brilliant. You can listen to this episode by simply pressing Play above, or wherever you get your podcasts including Spotify and Apple. And you can also read the conversation in this post, below.

Stephanie Shonekan is an author and musicologist who writes and teaches prolifically on music - from soul music, to country music, and Nigerian and African-American hip hop. Shonekan serves as the dean of the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Maryland, and we have created a podcast together, Cover Story with Stephanie Shonekan, at the University of Missouri and its NPR affiliate, KBIA.

Cover Story is all about life, history, love, identity, and music - through our culture’s favorite songs. And that is also what Stephanie Shonekan’s work is about.

In the course of our podcasting together it was exciting to discover that not only is Shonekan a huge reader and watcher of Austen and romance, but also her first degrees, her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, were in English and literature.

So: We talked about reading Jane Austen while growing up and going to college in Nigeria - and how the stories of Austen might play for young readers in Nigeria growing up and growing into life and literature. Again, it’s all about: culture, identity, love, and the stories we tell.

In this conversation, Shonekan talks about the fact that in Nigeria as a colonial and post-colonial country, she was introduced to characters and stories that did not reflect her family, her friends, and herself - and that was both an awakening of sorts, and also a painful thing to discover. Her answer? To go and find the authors and the classic literature of Nigeria, her home country. Enter: Classic writers like Chimamanda Adichie, Buchi Emecheta, Wole Soyinka, and Chinua Achebe. And she asks a very simple but powerful question: Why weren’t these writers introduced to her as part of her education? Why did she have to go and discover them for herself?

This is a question about the canon of classic literature - and how something that can bring transformation and joy, like classic literature, can also, and has been, used to disseminate power, nationalism and empire, and can be deployed to erase culture and identity.

Dean Stephanie Shonekan, in this episode, talks with us about discovering the stories of Jane Austen, and then discovering stories of her own. And then, finally, circling back to come to terms with the stories of Jane Austen. And also: Bridgerton. Because in any conversation about romance, race, and the stories we tell, we have to talk about Bridgerton, right?!

Enjoy this excerpt of our conversation:

Note: This post might be too long for email - but no worries, you can read the full post including the “links and community” section at the website, here.

Plain Jane

How did you first discover Jane Austen? Do you remember where you were? And when you first read a Jane Austen novel?

Stephanie Shonekan

Ah, I would say that I probably read Pride and Prejudice when I was an undergraduate student at the University of Jos, in Nigeria. Up to that point, we'd done a lot with my high school. In Nigeria, of course, because we are a British colony - we were a former British colony, I should say; Nigeria got its independence in 1960. But the aftermath of colonialism means that we continued to have English as the official language. And our educational institutions were built on the British system, which means that when I was in high school all of or most of our curriculum was British-based.

So a lot of Shakespeare - I remember reading Shakespeare, The Mayor of Casterbridge, Moll Flanders, those sorts of those classics of British literature, Heart of Darkness, all of that.

And then, when I got to university, I probably read Pride and Prejudice there. My undergrad is English literature. And then after my first year or two, when we were allowed to then take electives, I veered completely off and went to Black literature. I wanted to read more Nigerian literature. I wanted to read more African writers and also African-American and Caribbean writers. So I probably put Jane Austen in the same boat as Shakespeare and all of them. Great literature, great, great stories: But in my formative years, I really wanted to dislodge those images and stories that were not mine.

And move more towards African literature and African-American and Afro-Caribbean literature. So I went through a love-hate relationship with Jane Austen. But I've since come to terms with it. Have a real good grounding in Black literature, and can appreciate certain aspects of British literature as well.

Plain Jane

[L]et's first go back to just those early days. I mean, that is an education, colonialist education, that includes a lot of genius, but it's also being inflicted on students, young students. to make them think differently. And in some ways there has been erasure involved in that. Can you just talk a little bit about reading Pride and Prejudice in that situation? And then revisiting maybe Jane Austen later?

Stephanie Shonekan

Yeah, yeah. So it's really interesting to look back. I'm so glad we're having this conversation because it's causing me to sort of look back and see where my little moments of awakening were. And I would say I went through - when I was maybe late teens, mid to late teens - all of us young girls, young women, in Nigeria, so many of us would read these romance novels called Mills & Boon. They were published by this publisher called Mills & Boon. So we just called these books Mills & Boon. And they were all and then there was another author called Barbara Cartland.

Plain Jane

Oh, yes, yeah - those are like British traditions for sure. I mean, those are strong cultural forces!

Stephanie Shonekan

Yes, for sure. Devoured them. I mean, just thought they were so romantic. You know, we escaped into them. We traded these books with each other. A friend would come over, “How many Mills & Boon or Barbara Cartland are you bringing over?” And then we would exchange. This was a big part of my coming of age. Never really stopping to think that, you know, the characters in those books just, they don't look like us, you know? Like the idea that when they describe the man as tall, dark and handsome, they weren't, the writers never thought that that “dark” was Black people, you know, it was dark-haired and so on.

We traded these books with each other. A friend would come over, “How many Mills & Boon or Barbara Cartland are you bringing over?” And then we would exchange. This was a big part of my coming of age. Never really stopping to think that, you know, the characters in those books just, they don't look like us.

And so the fact that we consumed all of this, you know, without question. It's something that I look back on now. And I'm rethinking and really mourning, the lack of awareness or … the erasure of who we were. And what value was put on us as human beings. We never questioned that. No one helped us think through that. So I would say that Jane Austen and Shakespeare and William Wordsworth were seen as elevated forms of Mills & Boon. So there's romance in Pride and Prejudice, of course, and I mentioned that a lot, because that's the one I liked the most.

Plain Jane

I think that description holds. They're all elevated Mills & Boon!

Stephanie Shonekan

They are, they're just long, they're longer. And Jane Austen takes her time with it. Whereas with Mills & Boon: Girl meets Boy, girl gets mad at boy, boy figures it out. And then they're done. Very simple. And isn't that what Darcy and Elizabeth …?

Plain Jane

Absolutely, yes, Darcy and Elizabeth stripped down to just what it is we all love, stripped down to the sugar. Without the rest of the meal.

Stephanie Shonekan

Exactly. So while I met Jane Austen, in university, in an elevated way - because that was literature, that wasn't Pulp Fiction, that was literature, right? Those are the classics. I took them very seriously. I certainly enjoyed her more than I did Shakespeare for, you know, for whatever reason.

But the question remains: Why was that given to us as a classic? Whereas our Black literature was given to us as electives? That stays with me as a big question.

I know we'll get to Jane Austen, and what I love about her stories, and what I watch and what she did. But the bigger question for me is the place of Jane Austen over authors like Buchi Emecheta and Chinua Achebe. And what they’re showing, you know, why is Jane Austen higher on the totem pole than those authors?

Plain Jane

And I think that is a question that people in that, you know in the literature world and in the Jane Austen world, I do see that question coming up. I do see that being explored. But do you feel like it is, from what you've seen? Do you feel like it's being explored adequately? And what would you want people to keep in mind as someone who grew up in Nigeria reading Jane Austen, and having this, as you just said beautifully, just presented to you as the canon, as the Important-with-a-capital-I Work-with-a-capital-W, and then the Achebe and others as electives? But what would you hope that those conversations include?

Stephanie Shonekan

I think people are only moved when they're close to the problem. You know, and I think that unless academia really leans in to the canon, and really studies the canon to figure out why the canon is as it is, and how unfair and skewed the canon is, until we get there, these conversations, sure, will happen, but they will continue happening on the periphery. They will come, they will continue happening on the side. And you know, we'll have moments, you know, where we see it pushed in a little bit more by the mainstream - moments like George Floyd, right? But for the most part, it's an uphill battle. It's an uphill battle to try and sort of diffuse the canon and expand it to the point and reorganize it to the point where we can keep a Jane Austen in - because, again, really great stories - but that cannot be the only story.

It reminds me of Chimamanda Adichie in her talk on the power of the story, right? That that can't be just one story, that there are other stories. And until we can collectively find a place for all the stories, it's going to continue being a question that's being talked about on the side.

[W]e consumed all of this, you know, without question. It's something that I look back on now. And I'm rethinking and really mourning, the lack of awareness or … the erasure of who we were. And what value was put on us as human beings. We never questioned that. No one helped us think through that.

Plain Jane

OK … I hear what you're saying. I mean, it's easy to have conversations like this. And to see this as an extra thing. And it's about the need to change the default. Change how we view the default, but also realize that we have been faulty in our default, right? And what we're really talking about is a word that you and I have talked about recently, which is systemic. It's realizing that that default - that teaching Jane Austen in Nigeria - has been wrong. It's been skewed. It needs to be corrected in a very overt, systemic way. And that's hard. And that is more than podcast conversations. And it's also about having Black faculty. …

Stephanie Shonekan

- Yeah, all that is true. But it's also, so Jane Austen being taught as a requirement, you know, or British literature as a requirement in Nigeria when I was growing up: When do we ever see Achebe as a requirement? Or … any of these really wonderful writers? When do we see them as a requirement? In the West? You know, they're always an elective. When you find it, great. If you don't, if you're not looking for it, you're not going to find it.

Plain Jane

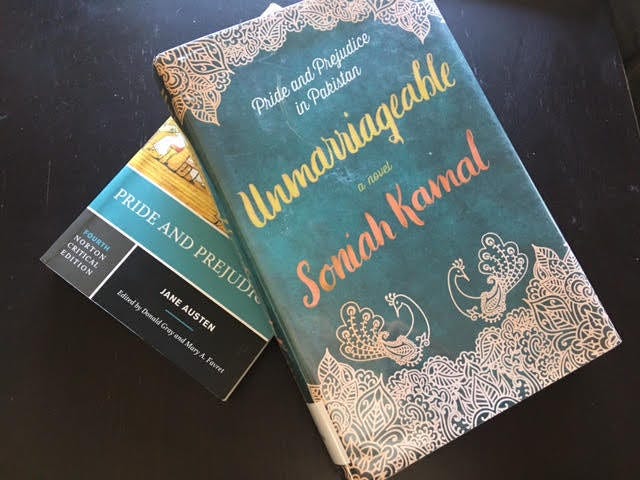

Well, let me let me switch back to … a little bit about the Mills & Boon, reading the Jane Austen: quick question on the Mills & Boon, all of you and your schoolfriends reading Mills & Boon and trading them, which is adorable to think about. Were you envisioning Nigerian leads? In your mind? I've talked to the writer Soniah Kamal [author of Unmarriageable: A Novel] who went to school in Pakistan, and she says …

Stephanie Shonekan

Yes, I read that on the blog … !

Plain Jane

Oh you read the blog! Okay, so she does a retelling of Pride and Prejudice. But by the way, her character of Darcy [Darsee] says exactly what you just said, which is kind of I think, what is being introduced to a lot of readers when they read Soniah Kamal’s retelling: He says, Why doesn't everybody have to read Pakistani literature? Like, why isn't that in the canon …? So it's just a big plug for sort of being more globalist in the canon… But [Kamal] says Jane Austen is Pakistani. Like, for her Jane Austen and all of those characters have and always have been Pakistani, or you're reading Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice for the first time in Nigeria. I think the characters would be Nigerian …?

Stephanie Shonekan

Not so for me. No, they were absolutely not. I mean, you look at how they're displayed: Their hair is described [in a way] that would never translate to a Nigerian woman's hair. Even the traditions, what happens, how people talk to each other, modes of communication. Not even just in terms of language, but also in terms of cultural signals. Those don't translate to, in my mind, to a Nigerian society at all.

When they describe her features as sort of pale, you know: the blush on her skin, and, you know, the deep blue of the eyes. I cannot read that and see myself or see anybody around me that remotely looks like that.

And so, for me, I found it very interesting that [Kamal] translated that to a Pakistani environment, it just doesn't fit. And that might be just me, because I'm - I don't know - too Black.

But when we read it as teenagers, we knew that wasn't us, you know. Like, we maybe didn't think of ourselves, but we certainly knew that they were white. Thinking about the way the hair is described. Her petite frame. Our frames are not the same. Our skin doesn't blush like that.

So it was an escape, it was certainly a way to see another world. What I would say we enjoyed was the idea of romantic love, which we saw in our parents. It was described, it was different. You know, we all wanted to be cherished, the way our hearts flutter when we see someone that we have a crush on. That's universal.

But the characters, the descriptions, the culture is very different and does not translate to Nigeria.

I always push back against this idea that there's a Black Jane Austen, or that these are stories that, again, with the standard being British, and then we have a translation to it. I kind of push back against that and remind us all that we have our own stories that are romantic stories as well but are going to be different in terms of how we are described, what beauty looks like.

A big part of Mills & Boon … is describing the beauty of the woman and the handsomeness of the man. And that's not what our beauty looks like. And that's been … at the heart of the problem when we think of systemic racism is, what are the aesthetics? What is beauty? And how, how do we see it? How do we describe it?

I always push back against this idea that there's a Black Jane Austen, or that these are stories that, again, with the standard being British, and then we have a translation to it. I kind of push back against that and remind us all that we have our own stories that are romantic stories as well but are going to be different in terms of how we are described, what beauty looks like.

And how do we then see it on our magazine covers? On our television? Newscasters? You know, what does hair look like? Why do young Black men or women have to shave their locs when they're wrestling? Right? Or when they're trying to to graduate? That is because of the ways in which beauty has been described for too long in literature, in film - and Mills & Boon and Jane Austen have a lot to do with that.

It's very complicated for me. Jane Austen is just telling her stories, right? Like this is - these are her stories. I'm not going to hold her responsible for being in the canon. It's not her fault that she's in the canon. It is the society's fault that she's in the canon without a counterpart that looks like me, right? That is not Jane Austen's fault. That is our fault. That is the fault of the Western academic enterprise.

A big part of Mills & Boon … is describing the beauty of the woman and the handsomeness of the man. And that's not what our beauty looks like. And that's been … at the heart of the problem when we think of systemic racism is, what are the aesthetics? What is beauty? And how, how do we see it? How do we describe it?

Plain Jane

Absolutely. Who were explicit. If you look at … Thomas [Babington] Macauley. It was used as a tool of power. Absolutely. … to prevent nationalities of all cultures from seeing themselves and from celebrating themselves and their power through art.

Stephanie Shonekan

So, that's on the one hand. On the other hand, you read this work, and you wonder, what about other people that were in this society? You know, you read Mills & Boon, or you read Jane Austen, or you read, you know, North and South, any of these books. And you wonder, “OK, like, where's everybody else?” You know, and are they not worthy of being characters in any of these stories? So it reminds me why - I know this is not a political show, Janet, but ,,,

Plain Jane

Well, it is! Actually it is - when you're talking about Jane Austen. And I'm just gonna say: Jane Austen would approve. She was definitely tackling politics. So go right ahead.

Stephanie Shonekan

OK! So it makes me wonder what people, what is meant by “Make America Great Again,” you know, when you think of the history of America and of the United States, and, sure, great for some people. But what about the other characters in American history? When was the country great for them?

So if you're going to use a tagline, “Make America Great Again,” I'm wondering: Who do you mean? … Where are the other people? Where are they considered in your vision? Right? Whether you're looking backwards, you know, or forwards.

Now to the adaptations: I love the adaptations. I mean, I will watch any adaptation of Pride and Prejudice there is. I love the Keira Knightley one.

Plain Jane

So this is actually maybe the most controversial thing we'll talk about today, Stephanie, which is: 1995 or 2005!

Stephanie Shonekan

Really?

Plain Jane

I like both of them. I am gonna be diplomatic. There's Colin Firth with the 1995 version., People younger than us just adore it, I think they consider themselves … the purists of the Pride and Prejudice [adaptations]. But, you know, if that caught you when you were 12 years old, and Colin Firth, you know, coming out of that lake in the white tunic and the wet shirt - [if] that caught you just at the right time, like, there's no going back.

But I like both, Stephanie. So OK, so you like the 2005. And the music in that one….

Stephanie Shonekan

Yes, Stunning. Stunning. I will listen to to that soundtrack while I'm doing my my own research or writing. I love the soundtrack. Because I watched that probably with my daughters later on. We just enjoyed that - one of my daughters in particular enjoys the British classics. And she’s reading them and so she and I have really enjoyed watching shows like Pride and Prejudice. Anything on Masterpiece.

So I guess we should talk about Bridgerton.

Plain Jane

Yes!

Stephanie Shonekan

Well, I think, again, I think it's more complicated than, you know, inserting Denzel Washington as Hamlet right? I think, Yes, I think that's great. I think that's a good step. I love to put the television on or go onto Netflix and see characters that are representative of the spectrum of humanity. I think that's wonderful.

Two problems, though: One is that it's still, these are still white stories. And when will we have Black stories or brown stories, you know, that are shared at that level? I found them … After the second year of my undergrad, I just focused mainly on literature of the diaspora, the Black diaspora. And so I found all those stories. And then into my Master’s. That's what I focused on: on the poetry of Langston Hughes and Amiri Baraka and so on.

So I found those stories myself. When can we see some of those stories on a mainstream level?

So Bridgerton - beautiful story, brown people, Black people, wonderful. But it's still a white story. … Bring the diversity onto the screen, onto the canvas. But are we paying attention to the stories of each of these people that we're putting on the screen? You know, what is the story of those two main characters and Bridgerton, second season? Like what happened in India? You know, what's that story? That's not what we're focused on. We're focused on her sister's quest to find an Earl, or whatever. But so that's one question.

And the other question I would have about these adaptations and Bridgerton in particular, is that we always stop short of darker-skinned characters. And [this might be] just my lens, I know not everybody wears the glasses that I wear. But when I watch Bridgerton, or whether it's season one or season two, if you look, if you zoom in and … we're looking at skin tone and … shades of skin - we never get to dark-skinned women. And that's just me. I have a chip on my shoulder because I am a dark-skinned woman. We never get those roles. We never get to see ourselves in that role. Yes, we might have a Black woman who is lighter skinned. We get that even in Bridgerton season one - the one Black woman, a woman who was lighter skinned … didn't have a main love interest; she was the one who got pregnant. And so on and so forth. So I don't want to [spoil it] for those who haven't watched it. Go watch it. It's a great series.

Plain Jane

Well, it's OK to have spoilers here. Because everybody here has already watched Bridgerton several times. I know that for a fact. I'm just kidding. … These conversations are bubbling up. And there's a lot of appreciation when those darker skinned characters become main character status. And some people would say that is happening with Bridgerton with the Sharma sister who's the lead and that actress as being a darker skinned brown actress than has previously happened apparently. But … What would you like to see in a third season of Bridgerton? … What would you as .. a scholar and researcher on art and nationality and race and somebody who engages with these joyful stories? What would you advise if Netflix called you in to advise on the third season?

Stephanie Shonekan

As a viewer, I would love to see, you know: Let's go darker. You know what? But I'm selfish, you know. I want my daughters to be able to watch a show that is so romantic and see themselves. That's what I would selfishly advise. I would love for my son to be able to see a woman that looks like his mother or his sister, be wooed in the ways that he has seen in every film that he has watched for white women. So I think that would be wonderful.

I want my daughters to be able to watch a show that is so romantic and see themselves. That's what I would selfishly advise. I would love for my son to be able to see a woman that looks like his mother or his sister, be wooed in the ways that he has seen in every film that he has watched for white women. So I think that would be wonderful.

Plain Jane

You are an amazing looking family, by the way, too. They're all like, really beautiful. So yeah.

Stephanie Shonekan

I think so too. But as an academic, as a scholar, I would love for the Bridgerton crew to actually continue on with Bridgerton, maybe finish it at some point and then look to other stories. You know, I think I would love to see a focus on stories from the Caribbean, from Haiti, from - again, selfishly - from Nigeria, from Trinidad, which is where my mother's from. There are some really wonderful authors that have written great stories. I know many of the stories are about struggle and liberation and so on. But within those stories, there are still relationships that happen. And Bridgerton actually is based on the on a contemporary writer, right? So there are historical novels by contemporary writers that are available on the other side as well. You know, there are some really wonderful African-American writers that are taking on those stories. …

Plain Jane

There's Vanessa Riley, who did Island Queen who's talked with us at the Austen Connection and she says that the actress who plays Lady Danbury in Bridgerton, Adjoa Andoh, with Julie [Anne] Robinson, also behind Bridgerton - they have optioned Island Queen, and Vanessa Riley's background is Trinidad and Tobago, and is writing the real life story … [of a] West Indian entrepreneur. …

Stephanie Shonekan

And they're coming, they're coming. So the author I'm thinking of is Alyssa Cole, who has done a whole series of books and the characters are mostly either freed slaves and enslaved people who were freed, or people who were born free. But it's definitely from that era. So set in the 1700s 1800s. And there's romance in there. It's a series that I've I've really enjoyed even though it's painful to think of that period …. So Alyssa Cole is someone that's doing historical fiction, romance fiction. I think that I would definitely recommend at the top of the list.

Plain Jane

And so if you’re from Netflix or Amazon Studios and you're listening ,,, we want those stories. We need those stories. … Vanessa Riley … said that a big problem - and you've heard this I'm sure we heard this from many Black artists and writers - that the problem is Black joy. People want the struggle, they want that story. And you said, those are painful stories … there's a lot of pain in Jane Austen too. It's not the same, of course, it's not at all the same. But there is marginalization, there is struggle. And so I guess it's just something maybe to remember - that the joy, whatever our real life experiences in history and any culture, in any place. There is love going on. There's romance. There's joy.

Stephanie Shonekan

Yeah, absolutely. And you see the joy and the love in our music. You just don't see it as much in the literature, in the film. But the music saves us because it's right there.

I don't think there's any genre or group of people that have put love in music as much as Black people have.

And thank you, Austen Connection friends, for engaging with this conversation.

Check out some amazing links, below, to contemporary and historical narratives featuring Black stories told by Black authors, including the ones referenced in this conversation and a few others we didn’t get to.

Friends, we’ll continue to look for Black, BIPOC and authors of color from every age and era to expand our understanding. our representation, and our pleasure in classic literature, history, romance, art, and the novel.

Help us do this! Do you teach a classic or contemporary novel from a Black author alongside your Austen in the classroom? Anyone out there teaching The Woman of Colour, or Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s Iola Leroy alongside Austen, expanding the canon? Or do you have other recommendations of Black, BIPOC and authors of color writing their own stories in a historic, Regency, or other settings?

Let us know - right here! And check out some of the amazing links below for more.

Meanwhile, enjoy your P&P 1995, your P&P 2005, enjoy your Bridgerton, enjoy your Loyal League series by Alyssa Cole, and keep reading, watching, and listening,

As ever yours,

Plain Jane

Links and Community

The Woman of Colour: A Tale is a Regency story published in 1808 chronicling the life, love and adventure of a Black heiress, Olivia Fairchild, who travels from a Jamaican plantation to 19th century England to marry. Here’s a wonderful edition from Broadview Press published in 2007 with historical notes by Professor Lyndon Dominique. Some teachers are including this book alongside Austen, directly addressing this issue of the canon of literary works and what gets taught - let us know if you are doing that and how it went for your class. Also check out the 19th century Black novelist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper’s novel set in the Civil War, Iola Leroy.

Stephanie Shonekan references Nigerian literary classics, including: Buchi Emecheta, Wole Soyinka, Chinua Achebe, and Chimamanda Adichie,

Patricia Matthew is a well-known author and professor whom many of you in this community know and love. Professor Matthew has written about her complicated feelings about reading Jane Austen, with “On Teaching, but not Loving, Jane Austen,” and on Bridgerton here, and on how she embraced her inner Emma - who can relate?!

We also talked about the writing of Alyssa Cole and her historic and contemporary romance fiction. Here’s the Loyal League series featuring romances set in the Civil War among a network of Black spies working to overturn the Confederacy.

Here’s Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s talk on The Power of Story:

Coming up Nov. 4/5 - Austen Con: Regency sisters breaking rules!

Join Devoney Looser, author of The Making of Jane Austen, for a lively conversation and a live taping with us, the Austen Connection podcast at AustenCon 2022, next weekend, Nov. 4th/5th! We’ll talk about Regency women writers in action and Devoney’s new biography, Sister Novelists: The Trailblazing Porter Sisters, Who Paved the Way for Austen and the Brontës. You can get tickets here. This is a fantastic book, I am SO HOOKED - you can order the book, which just dropped this week, here. And my final question: When can we watch the Sister Novelists Netflix series?!

If you enjoyed this post, feel free to share it!

Reading Jane Austen in Nigeria