Hello dear friends,

Welcome to another week of The Austen Connection and our sixth podcast episode, which you can stream from right here, or from Apple or Spotify!

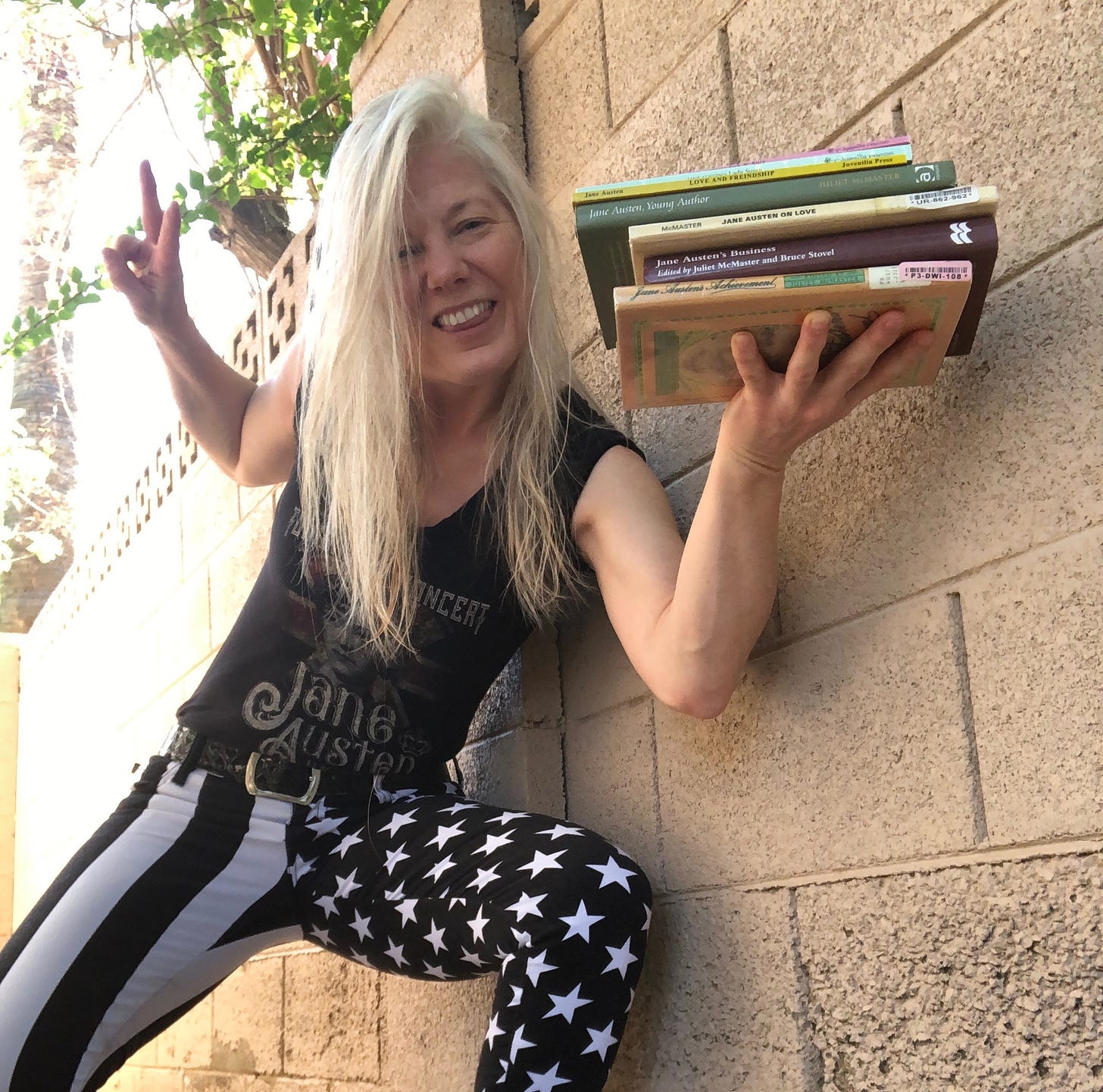

And this episode features a conversation with Austen scholar and Janeite Devoney Looser - who for many of you captures the spirit and vibe of Jane Austen’s stories in her work and in her life:

Looser has dedicated so much of her life to connecting through literature and Jane Austen, from her books, her teaching, her many appearances at conferences and at Janeite and JASNA gatherings, and also in her personal life through her marriage to Austen scholar George Justice and her roller derby career as Stone Cold Jane Austen.

These days Devoney Looser is working on a new book, due out from Bloomsbury next year: Sister Novelists: Jane and Anna Maria Porter in the Age of Austen explores two sister novelists writing, innovating, and breaking rules in the Regency and Victorian eras.

Devoney Looser is also the author of The Making of Jane Austen.

And - full transparency here - I’m lucky enough to call Devoney Looser a friend. We met as professors on a campus in Missouri. So this is a continuation of conversations that Devoney and I have had for years. We got together by Zoom a few weeks ago and talked about many things, including the first time she read Austen, how an Austen argument was the foundation of her first conversation with her husband, and how - just like Jane Austen - Devoney straddles the worlds of both high culture and pop culture.

Here’s an excerpt from our conversation. Enjoy!

Plain Jane: So let me just start if you don't mind with a couple of just questions about your personal Austen journey. What Austen did you first read? When did you discover Austen? Do you remember which book? And which time and place?

Devoney Looser: Absolutely. And this is a question that I really enjoy. It's a kind of conversion question, right? … So I love that this is where we start … I do have my awakening moment. And your awakening, I think this is a common story for a lot of Janeites, which is why the story resonates. It was my mother, who handed me a copy of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice bound together. I now have this book. It was a Modern Library edition of both of those novels that was published in the ‘50s. And she handed it to me because … she knew I was a reader, she knew I loved to read. And she said, “Here's one that I think you should read.”

We had books from her childhood, or from church book sales in our house, we had a lot of books in our house. And I started to try to read it. And I really stumbled because I could not get at the language. But she was insistent, she kept kind of putting it toward me, and saying, “I think you should read this one.” And I think it was maybe around the third time I tried it - Pride and Prejudice is what I started with - it just really took. You know, it was like, Oh, wait this is kind of funny. And I like these characters. And I like the story.

So after I got my PhD, I learned that my mother had actually never read Pride and Prejudice before. And to me that actually made her giving it to me even more meaningful. She is not college educated. She wanted me to have an education. And the idea that novels could be handed down from mothers to daughters, even mothers without an education, to say, “Here's a way for you to have access to more opportunities,” is what the books are about too, in a way, right? I mean, the mothers aren't always the ones doing it in the books. In fact, they're often not. But the books are functioning as that opening up - worlds opening up possibilities and opening up education, self actualization. You know that this is to me meaningful that my mother knew that this is a book that educated girls should read, and that she wanted it for me.

Plain Jane: She was tapping into something that she hadn't had herself and just trying to give that to you. That's awesome. So you're a professor, scholar, writer. … What attracts you to the conversations about Jane Austen, and teaching Jane Austen?

Devoney Looser: I think the thing about Austen that keeps me coming back to her is how readable she is. And lots of people say this in the critical community and the Janeite community like the scholars and JASNA. I think even anyone who picks her up casually having not read her in 20 years or never read it before, there's a complexity there on the level of the sentences, paragraph, plot, that is really, to me. enriching, or generative - it generates ideas.

And every time I go back to the books, I see something new. every age, every experience that I've made it through, gives me a new way into those sentences. And there are a lot of books that we love, but that we can't really imagine rereading with the same level of love, I think. And for me, that makes Austen just really remarkable. The idea that you can go back to her, you know, every year. A lot of people who love her books read her every year, all six every year. Do you know that joke from Gilbert Ryle, the philosopher, philosopher Gilbert Ryle was asked, this is a century ago, asked, “Sir, do you do you read novels?” And he said, “Yes, I do, all six every year.” So this is this is a good Janeite in-joke, that the only novels there are these six? Obviously not true. … But the relatability is how I would I would answer that.

Plain Jane: So I mean, Jane Austen can be, like you say, kind of adapted to your life as you go through different things in life. But you, with The Making of Jane Austen have really documented how not only individuals can adapt Jane Austen to their lives, but movements can adapt Jane Austen to their causes and ... we see that in kind of exciting ways. Can you talk a little bit about why her? Why are her novels so adaptable throughout the last couple of hundred years?

Devoney Looser: So I know you know this, I talked about this in The Making of Jane Austen about the ways that various people have very different political persuasions find a reflection of their values or questions or concerns in her novels. So she has been used to argue opposing sides of political questions for 150 years and probably longer. I think this was partly to do with the fact that her novels and her fiction open up questions more often than they close them. And I think it's her relationship to the didactic tradition in her day, the moralizing tradition. I think she's really stepping outside of that and more interested in gray areas, than in declaring what's right and what's wrong. So I think this is a beautiful, complex thing about her novels and they’re novels of genius, to my mind, and I'm not afraid to use that word. But they also present certain kinds of really interesting challenges, because you can't go to them and say, “What should I think?” They don't really answer that question for you in a clear away. I think in other kinds of didactic fiction where there's a clear moral outcome, this person's punished with death, or, you know, or some kind of tragic outcome, or this person's rewarded, and it's all going to be, you know, happily ever after, and nothing ever is going to go wrong. Her novels are working outside of that to some degree. So I do think that that's one reason why people have very different experiences and political persuasions and motivations, come to her novels, and it can be kind of like a Rorschach test, right? You can see what you want to see in the designs to some degree. Now, I do think people can get it wrong, I think you can find there are arguments that people make that I think there is absolutely no textual evidence for that whatsoever. But oftentimes, I can look at someone coming to a conclusion that might be different from the one that I reached, and say, Well, I see where you can get that from emphasizing this point, more than this one, or seeing this passage as the crucial one, instead of another passage.

I think this is a beautiful, complex thing about her novels and they’re novels of genius, to my mind, and I'm not afraid to use that word. But they also present certain kinds of really interesting challenges, because you can't go to them and say, “What should I think?” They don't really answer that question for you in a clear away.

Plain Jane It's also occurring to me listening to you Devoney, that she sort of makes people think, in ways that might be uncomfortable. She must be one of the few novelists that can actually draw you to her story, draw you in and draw you to that narrator. But also be uncomfortable, maybe with what she's giving you. And maybe we just stepped around the discomfort some of us. Do you think that's an accurate way of thinking about Jane Austen as well?

Devoney Looser: I think that's beautifully put. And, you know, I think too we can read her novels on many different levels. If you say, I want to go into this for a love story, that's funny, with a happy ending, which is what many people who read in the romance genre know the formula, and they're going to it because they like the formula. And it might have different things in different component parts. But you know that at the end you're not going to be distressed and dealing with something tragic, right? So when you go into an Austen novel, the kinds of discomfort you're describing, that they will be there along with something happy, too. So I think you could just read it for the happy ending. [But] I see that as a real lost opportunity. Because I think the happy endings are tacked on from genre expectation about comedies. If you're focusing on the happy ending, you're missing all the important stuff that's happening all along the way. And that's the uncomfortable stuff, right? The stuff about family conflict, economics, all of the kinds of ways that people are terrible to each other, that are, maybe borderline criminal or actually criminal. But everything below that, too. That's more mundane, the way that people mistreat each other. That is wrong. It's not criminal. And that, to me, is what makes these novels uncomfortable, is that even those people who are doing terrible things, usually get away with it.

Plain Jane: Hmm, yes. If you said to people, Here's a novel about the insult and injury endured by women because of class and gender - and possibly you can add race and disability and a lot of other boundaries in there” - I don't know how many people would see that as Jane Austen. But there's that subtext. … The more I read and reread Jane Austen and just stay really close to the text, the more I find myself relying on Gilbert and Gubar and their “cover story.” And it's, you know, I read that a long time ago. So it's probably influencing my reading, I say close to the text, but it's close to the text that's very influenced by what I already have read of you, and is it Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar…. How much do you think she was consciously or even unconsciously saying stuff? In all that meandering, within that courtship plot and then within that happy ending plot that you just described? How much do you think was going on with that cover story?

Devoney Looser: So I want to first start with the end of this, which is to say, I think every sentence is saying something else. You know, and not like it's a secret ...I think there are there are people who will say that this is a code for a completely other world below the surface. I'm not sure that I would go there. But I do think that these are novels that are trying to get us to investigate not only who the characters are, but who we are. And sonthere's always something else going on in any human conversation. There's always something else going on. And I think she captures that in the conversations among her characters, that they can be having the same conversation but with such varying motivations that you can see it and it becomes humorous. You know, Henry Tilney in Northanger Abbey, talking to Mrs. Allen, about Catherine Morland’s chaperone about muslin, that whole conversation about clothing and shopping. You can read that as a love of fashion, you can read it as an indictment of consumer culture, you can read it as a kind of gender cosplay, or you can use it as an indictment of femininity. I mean, there's just so many different levels within the same conversation and you can try to understand how these characters are arguing with each other. So I think in some ways, what you're getting at is, Yes, there's something beneath the surface.

So the text that you brought up, Gilbert and Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic, I think that came out in 1979 - incredibly important book. Because a lot of second wave feminism, 60s and 70s, had said Jane Austen is not a primary author for us or not an author that can be as important to the second wave, because these novels end in marriage. And it was a moment in the feminist movement, when looking for something that expressed anger, that expressed alternative lifestyles, was seen as more important than reinforcing heteronormativity, which is what Austen was imagined as doing. So what I think what Gilbert and Gubar did is allowed for feminists and feminist critics and scholars and people beyond that circle, to look at Austen and say, “What if we didn't emphasize the ending? What if we emphasize the other parts of the story?” And of course, they took that to a lot of other different texts and the “madwoman” in the attic is actually a reference, as you know, to Jane Eyre, to Bertha Mason? What if you read Jane Eyre and centered Bertha Mason, which is of course exactly what Jean Rhys did in her novel Wide Sargasso Sea. But Gilbert and Gubar gave us a framework to say, “Let's look at the parts of these novels from a feminist perspective that maybe we haven't focused on.” And I think it opened up so much possibility for Austen, reading it through that lens of saying,”Maybe there's more here than the ending. Maybe there's more here than heteronormativity. There is a lot more going on.” And I'm really grateful to that book for doing that. I do think there is some tendency now to turn it all into, “Well, it doesn't mean this, it means this exactly the opposite.” To me, that's doing exactly what we shouldn't be doing. We're just closing down the text. … “Here's a clue. Now we'll find an answer. Now we've got this new clue, solve next mystery.” These are not mysteries with solutions. They are moral quagmires - and you can't solve a moral quagmire with a fact or an answer.

Plain Jane: I love that. I love the way you say, “Don't shut down the text.” I love the way you describe that 1979 Madwoman in the Attic, because you're right. They were just, I guess at a time when you know, feminism was wearing Doc Martens and reading Hemingway …

Devoney Looser: … and reading Kate Millett and Sexual Politics: Let's find the sexism. It was a sexism-identification moment, which is really important because a lot of people couldn't see it until people like Millett and others said, “Oh my gosh, there's sexism here in every single book, how do we not notice this?”

Plain Jane: Yeah. And they were saying, These are women's lives, let's interrogate what's happening with stories by women, about women, really going in depth in their lives. And they happen to be genius, as well. You know, Devoney, you also say, in your book, The Making of Jane Austen, that Jane Austen has, in many ways, been the making of you. This is getting back to you a little bit, Devoney. In what ways is Jane Austen and the making of you? I know a few of those ways. But why did you write that?

Devoney Looser: Well, I think, again, this is the reason this story resonates with people is because all of us who care about literature, and who allow books to lead us places, probably had moments like this. Mine is slightly more bizarre than most people's in that I now make a living from reading Jane Austen. And as you said, I read lots of other things, too. I read Jane Austen in the context of the history of women's writing, which has been very opening up of territory for me as a scholar, and I help lead people to read outside of her. But I've also been able to create a romantic life that started around conversations with her - and I know you know, this - that I met my husband, George Justice is also an Austen scholar. We met over a conversation and an argument on Jane Austen's books.

Plain Jane: What were you arguing about again? What book? Was it Mansfield Park?

Devoney Looser: It was Mansfield Park. So my husband George and I were introduced at a cocktail party that I was crashing. … And George had actually been invited. And we had a brief conversation that ended, but he came and found me because somebody said to him that I had worked on Jane Austen. And so he said, “I hear you work on Jane Austen. What's your favorite Jane Austen novel?” And I know, you know, George, Janet. So you know that he likes to ask these kind of puncturing questions, right. … … And I said, “Well, the one that I'm working on right now is Northanger Abbey.” And he said, “I didn't ask you which one you're working on. I asked you which one's your favorite.” He heard that I was working on it. But he wanted me to make an aesthetic, you know, you want to make a judgement about which one's the best. … So I said, Well, I guess my favorite is Pride and Prejudice. And George said very proudly, “Well, my favorite is Mansfield Park. … And so I said, “Well, Mansfield Park is my least favorite. And I like it the least because I don't like the heroine. Fanny Price is too much like me. She's boring.

Plain Jane: You said that?!

Devoney Looser: Yes. And George said at that moment that he said to himself in his head, “I'm gonna marry this woman.” So you really need to hear his side of it. I just thought, this guy's kind of needling me. And I'm shutting down his meddling with, you know, disarming honesty and sarcasm.

But you know, I do mean it, I did at the time. I really felt like a very shy person and quiet person and I had more class sympathies with Fanny Price of all of Jane Austen's heroines. But I didn't like those parts myself. I didn't like being quiet and timid, and didn't appreciate her as a character, I think, in a way that I now do. But he did end up proposing to me that night. And I said, “No.” I said, “I don't believe in the institution of marriage.” But whatever. What I can say is that he was very persuasive. And within about a month we decided we'd have a Jane-Fairfax-and-Frank-Churchill-style secret engagement. And we got married. We got married about a year later. So George is very persuasive.

Plain Jane: That's awesome. I did not know that he had proposed and that you had declined on that same evening. And I love it that you relate to Fanny Price and find that kind of complicated. Now I have to say, you have told me that story, Devoney. And I had forgotten the details about Fanny Price. But I learned them again, from the First impressions podcast, where they were talking about you on that podcast, and that you related to Fanny Price. And that got me thinking about who people relate to in Jane Austen novels. And I feel like Jane Austen is putting herself - I feel like all authors, for much of the time - are putting themselves in not just the positive aspects of characters … She's even probably in Mrs. Norris a little bit, you know? Think of your worst person, you know? There's a part of her that wants to be Lady Bertram, probably. And there's certainly a part of her that's Fanny Price. And there's certainly a part of her that's Emma, who's also a difficult character. So anyway … does George love Fanny Price?

Devoney Looser: I think George loves underdogs who triumph. And I think to him, he likes the idea of people who weren't born to it sticking up for themselves. And he likes the idea of there being greater opportunity for people who weren't necessarily born to opportunity. And I think that's the story of his grandparents and his parents. So I think that's where he came to the love of that particular plot, out of stories from his own family.

Plain Jane: So we are talking about, we've been talking about, the way people take on Jane Austen for their causes. You also talk about the fact that Jane Austen has ... carried pop culture and high culture simultaneously. Almost maybe like almost no other artist, maybe Shakespeare can carry those two at the same time. And you also walk both of those worlds. Can you talk a little bit about that? How are we doing with those two things right now? I mean, Jane Austen's probably bigger than ever before, right, today? And are we kind of bringing the high culture of the scholarly and the fandom together in interesting ways? And in productive ways?

Devoney Looser: Yeah, that's such a great question. And the “greater than ever before,” quite possibly, if only because of how communication is greater than ever before, right? … But there were moments where she definitely popped in popular culture before now, you know, millions of people saw that Broadway play in 1935 that moved to the West End in London, the next year. This was another moment of Austen pop culture saturation. Where I think if we were able to compare it, then, to now we might say she was in the imagination of the cultural imagination to a pretty great degree in these other moments, too. But let's not go there - now I'm in the weeds! But I do think there is something about being in both worlds that really speaks to my sense of our responsibility as scholars to be educators, but also to be trying to understand the world outside of the academy and seeing that as a talking across, not a talking down. And there are moments where it's easier for scholars to remember that than others, but the talking across has really made new scholarly ideas possible. For me, this is a divided identity. I think you're capturing that accurately in how you describe it, Janet, but I want to make sure that I'm saying it's not a one way street for me. When we talk about teaching, those of us who are educators, we talk about learning from our students, and people often roll their eyes at that … But I think back to an old, classic and educational theory of Paulo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed, where he talks about differently located learners. And the Janeite community through JASNA has definitely brought home to me the ways that differently located learners can inspire each other, and teach each other. And I think that is just really, really crucial. And I love that Jane Austen has made this possible.

Plain Jane: You know, we're in a way a lot of what we're talking about is her image. And how, you know, there's a lot under the surface of the Courtship and the Marriage Plot, that you've researched this, and written about it in The Making of Jane Austen. In what ways did her family contribute to this image? Can you talk a little bit about that? And why - why were they trying to create, if I have this right, a respectable sort of Aunt Jane? Do you feel like this is what she also would have perhaps wanted? I mean, class insult, class injury can be humiliating, and I feel like perhaps also Louisa May Alcott, some of these women writers who were writing for money, maybe did want to be seen first and foremost, as respectable. What do you think was going on with the family members painting her image?

Devoney Looser: I think this is a really difficult, multi-layered question. And I, of course, have different ways of answering this. But I think that the ways that her family described her, were trying to head off criticism. And I think if you look at the ways that women writers were treated in this period, you can understand why they wanted to head off the criticism. They very much wanted her not to be seen as strident Bluestocking, morally suspect. They very much wanted to put her on the side of … the polite, the proper, the lady .... Not the bitter spinster, not the ugly woman who couldn't get married or who was having all sorts of morally questionable behaviors with men. But the woman who was very much doing the “femininity”, quote-unquote, 1810s and the 1820s. So at first, I think that's what her family is up to. And the extent to which she would have been excited about that, I don't know. But it does seem quite possible that she would have endorsed staying to the side of that. Because in the same way that 70s feminists brought us to see the ways that language was about Virgins and Whores - not that no one had ever noticed this. But I think in Second Wave feminism, the Women's Studies classes, let us look at the words that were used to describe women and their sexual experiences, and say, “Wow, this is really unbelievable,” right? So I think if we take that and we move that conversation back 150 years, I think the Austens were wise to the fact that you were not allowed to be anything other than one or the other. And it was very clear what you wanted to be if your choice was to be castigated as the woman writer so who is more virgin-like, or the woman writer who is more Whore-like, of course, she wanted to be on the side of the Virgin. It's a crime that this existed, right? It's a linguistic crime. But if you're a family trying to negotiate the reputation of your relative at the same time that some of you are clergymen and trying to make your way forward in polite society, titled society, elite society, of course ... She's a Public Woman. Those words aren't supposed to go together. You want to put her to the side of the one who wasn't looking for money, the one who wasn't looking for fame, the one who wasn't too learned. She was nice. She was doing this for her family. She wasn't doing this for fame or money, you see that? Already, you're talking about sides of a question, where putting your eggs in one basket results in a different outcome. So the extent to which Austen herself wanted that, what would be desirable of being on the other side of that? Very little, right?

Plain Jane: Listening to you talk makes me really understand that so much more. And also realize that in a way they were doing what Jane Austen seemed to do with her novels, which was to keep herself out of it. And maybe she's not as out of it on the third and fourth rereading as we thought she was on the first rereading. But she's kind of keeping herself out of it and just letting the story, letting the characters, say what she really doesn't want to be seen saying particularly, perhaps.

Devoney Looser: You know that I'm working on two contemporaries of Jane Austen, Jane and Anna Maria Porter. I'm writing this book, Sister Novelists: Jane and Anna Maria Porter in the Age of Austen. And where for Austen, we have 161 letters of hers [that] have survived. So when we try to say, “What did Jane Austen think?” The novels give us a certain amount to go on. But a lot of us say, well, “What did she say in her letters where we can assume that she was being more of a quote-unquote, authentic self?” … But the idea that we only have 161 of these to go on; for the Porter sisters, they were both novelists. And they wrote thousands of letters, which they painstakingly preserved. And so to be able to go through these thousands of letters between these two sisters who are looking at literary culture through the eyes of public women and literary women, and looking at the ways that they describe the things that they want people to believe and what they're actually doing behind the scenes, has been really illuminating for me. And I hope other people will be interested in reading about that too, people who are interested in Austen, people who are interested in the early 19th century and Regency culture, Victorian culture, because the Porter sisters lived longer than Jane Austen did. [And] the ways that they tried to navigate making decisions with agency and with, specifically, female agency and romantic agency and a culture that said that, as Austen puts it, their only power should be the power of refusal. And they, the Porter sisters, were doing things all the time that you weren't supposed to do. And we know it because they were writing about it with each other. They were innovators in historical fiction. And Jane Porter claimed, I think with with some accuracy, that she was the one who influenced and inspired Sir Walter Scott's Waverley, which was published in 1814.

Plain Jane: Wow, you had us at Hello - our sisters writing to each other, during the Regency and beyond, and they have each other, they're doing historic fiction. I mean, I just think hashtag-Regency is going to blow up over these two sisters! I think that sounds like a lot of fun. I just feel like there is a hunger to broaden out these conversations, and you can see it, the conversations are being broadened out in such exciting ways, especially right now. Books, like The Woman of Colour, and then every conversation we can have about Bridgerton - like anything to do with the Regency and people's lives and especially the lives that we’re uncovering that have been overlooked: Women writers, Black citizens of the Regency in Britain, and it's just and so many others. It's just really exciting. So I feel like there's a hunger for these conversations.

Devoney Looser: And I think it's absolutely crucial and important that we start to try to understand race relations in the early 19th century. And think about why we care about them so much. Now, that's what literature should do. I get really frustrated when people want to tell us that we're taking questions from the present and popping them back falsely under the past. This is not at all we're doing. Things are popping in our moment that we can see, we’re also popping in Austen's moment. ,,, Maybe she doesn't write about them to the degree that some of us would now wish she had. But these questions are there. And we are having a real opportunity, through scholars like Gretchen Gerzina and Patricia Matthew, and others who are helping us look back to the abolition movement, look back to texts, like The Woman of Colour, which Lyndon Dominique edited in a fabulous edition for Broadview Press that everybody should run out and buy. This is a novel from 1809, an anonymous novel. All of these works are giving us new opportunities to read Austen in terms of race issues that were important in her own day and to her novels. And for very good reasons have popped up in ours, so I'm excited about the opportunity to open up these questions.

I do think there is something about being in both worlds that really speaks to my sense of our responsibility as scholars to be educators, but also to be trying to understand the world outside of the academy and seeing that as a talking-across, not a talking-down. And there are moments where it's easier for scholars to remember that than others. But the talking across has really made new scholarly ideas possible.

Plain Jane: And some of this is historians also - Gretchen Gerzina, in a previous episode, alerted me to the National Trust report that was done documenting the ties to the slave trade in the Great Houses in England. Such a simple thing, really. And very much a historic enterprise, not a political enterprise in any sense, other than [that] everything is political. But that's exciting. And then you've also contributed to this conversation about the legacy of slavery and the ties to the slave trade in the Austen family. Do you want to talk about that at all? I mean, this is something that's just been published in The Times Literary Supplement and then picked up a lot of places. Do you want to just give a takeaway on what was going on with your research on that and what you'd like people to keep in mind when they think about Austen's family and the slave trade?

Devoney Looser: Absolutely. So the May 21 issue of the Times Literary Supplement, which is a weekly newspaper that anyone who cares about literature should subscribe to … I am very honored to have published it. I did a piece on Austen and abolition, looking deeply and very minutely into the Austen family's relationship to slavery and abolition. And people are asking a question now, “Was Austen pro-slavery or anti-slavery? Was the author’s family pro-slavery or anti-slavery?” And because of things like the National Trust report that you just mentioned, and a freely available database called the Legacies of Slavery that's run out of UCL by a scholar named Catherine Hall and a team. This is a freely available database, George Austen's name shows up in that database, because he was a trustee for a sugar plantation in Antigua that was owned by somebody who was probably a student at Oxford. So this is the fact that we had, and that has been repeated, that Austen's implicated in the economics of slavery. And what my piece did, is tried to look at what that means, and to try to deepen that conversation. And what I, the takeaway, for me is that the Austen family can be described as both pro-slavery and anti-slavery. And this is probably true for a lot of 19th century families, frankly, where you would have members who were on different sides, quote-unquote, of these questions. But the moment we try to turn it into sides, we're missing an opportunity for further description and nuance. And what my piece shows is that George Austen probably never benefited financially from this trusteeship. He was a co-trustee. And I go into a lot of description about that. And that years afterward, 80 years after that, Henry Thomas Austen, we never noticed this before: Henry Thomas Austen was a delegate to an anti-slavery convention. So we have a member of the immediate Austen family, a political activist, against the institution of slavery and with the anti-slavery movement. So to me, this tells us that the Austen family was both of these things. And I think it's an additional piece of information for us to understand the ways that race and slavery come into Austen's novels and the ways that she is working with the difficulties and complexities of this issue that was central to the moment she lived in.

Plain Jane: What do you love most about introducing people to Austen? And what surprises you when you teach - in the classroom, or in Great Courses, from people that you hear from all the many Janeite and fandom conversations that you so graciously, drop in on Zoom with? What do you love about introducing people to Jane Austen?

Devoney Looser: Yeah, so these 24 30-minute lectures I did for the Great Courses, which is interestingly just rebranded itself as Wondrium. But I say there, and I say this at the beginning of my classes as well: I love these books. And I love the ways that these books have inspired me to be a better thinker and have created certain things in my life that have become possible and meaningful to me. But it is absolutely not required to me that anyone in my class come out loving them like I do. What I want is for students to find that thing that is meaningful to them. And that generates meaning for them - that's generative, to go back to that word again. And I think when students take me at my word, I'm very grateful. I want them to read closely and think about these things. But it is absolutely not required that they see in them what I see.

—————

Thank you for reading, listening and being here, my friends. Please stay safe and enjoy your remaining days of summer. We’ll be back next week - and it’s all about my conversation with definitive Austen biographer Claire Tomalin! I caught her at home, safe, enjoying her garden during the pandemic, and I’ll share our conversation here, same time, same place, next week!

Below are many of the authors that Devoney mentioned in this conversation, with links to finding out more.

If you enjoyed this conversation, please do share it!

And if you’d like to have more conversations like these dropped in your inbox, subscribe - it’s free!

More Reading and Cool Links:

Gilbert and Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic: https://www.npr.org/2013/01/17/169548789/how-a-madwoman-upended-a-literary-boys-club

Paulo Freire and The Pedagogy of the Oppressed: https://www.freire.org/paulo-freire/paulo-freire-biography/

Gretchen Gerzina - https://gretchengerzina.com/about-gretchen-gerzina.html

Lyndon Dominque, editor: The Woman of Colour: https://broadviewpress.com/product/the-woman-of-colour/#tab-description

Patricia Matthew: https://www.montclair.edu/newscenter/experts/dr-patricia-matthew/

UCL slavery database: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/

Devoney Looser’s website: http://www.devoneylooser.com/

The Wondrium/Great Courses on Jane Austen: www.thegreatcourses.com/janeausten

The Podcast - Episode 6: Devoney Looser on Living, Loving and Arguing About Jane Austen