Hello dear friends,

If you’ve watched the wildly-popular Netflix series Bridgerton or the wonderful film The Personal History of David Copperfield starring Dev Patel, you might have experienced and appreciated what today’s podcast guest saw: People of color in a fictionalized dramatization of 18th and 19th Century Britain. But in Gretchen Gerzina’s case - and unlike most of us - she knows the back stories of the real lives of Black residents of Britain in those eras.

Professor Gerzina says she is drawn to “biographies and lives of those who cross boundaries of history, time, place or race” - that’s on her website - and her work is all about this.

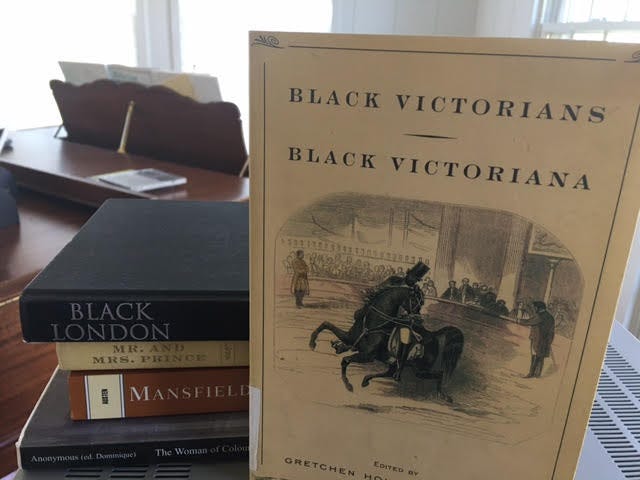

In books like Black London, Black Victorians, and Britain's Black Past, Gerzina bridges all of those boundaries for us - connecting us to people across time, place, and history - and introducing us to some of the Black performers, memoirists, activists and everyday people in Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Professor Gerzina joined me a few weeks ago, by Zoom, for today’s Austen Connection podcast, and we talked about the lives of some of these Black residents of Britain historically, how she is helping to tell the stories about their lives, and how contemporary fictionalizations of Regency England capture these stories, or not.

Enjoy the podcast - and if you prefer to read, here’s an excerpt from our conversation.

Plain Jane

So, I have been poring through your books, and I really enjoyed Black London [among others]. And … it's just really beautiful the way that you write about what you're doing - reconstructing, repainting history. In a way, you say, to illuminate the unseen vistas of people and places that are part of British history and part of our world history. Really illuminating the stories of the people and the community of Black women and men in [the] Regency era in 18th and 19th century Britain. So would you just talk first, Professor Gerzina, about that, illuminating the unseen? In what ways has this history been erased? And in what ways are you still trying to uncover that history?

Gretchen Gerzina

So that book was published 25 years ago or so and it's still being read all the time. And in fact, it's available as a free download through the Dartmouth College Library. And it stays in people's minds. The reason I wrote it was that I was actually working on a very different book. And … I went into a bookshop, a very well known bookstore in London, looking for … Peter Fryer’s book called Staying Power, the history of Black people in Britain - massive book. And it had just come out in paperback. So I said, “Oh, let me go buy that.” And I went into the bookshop, and I couldn't find it. And I finally went up to a clerk. And I said, “I'm looking for this new this book. It's just been released in paperback.” And she looked at me and said, “Madam, there were no Black people in Britain before the Second World War.” And I said, “Well, no, that's not true.” .. .

So I got so angry. I never found the book. I mean, I went to another bookshop, and it was right there. But I got so angry that I went home and put aside the book I was working on and wrote Black London. Now, I wasn't the first to write about this. Other people have written about it. And I wanted to both consolidate some of their research, go back to their research, and really look at everything that I could find. And then try to tell the story of Black people living in England.

It was supposed to be called Black London. It was called Black London here but in England it was published as Black England. And of course, the reviewers all said, “Well, this is all about London. Why are you not calling it Black London?” which was amusing. …

But I wanted to make people see … that these people are walking the same streets, we're living in the same neighborhoods. And I wanted to make it a living, breathing history. Now a lot of other people are working on this now and have done for a long time. But when I first started working on it, there weren't as many. And it wasn't known. And even now, it's not so much that it's been erased, as has been forgotten. People didn't quite realize that there had been a Black British history that goes back as far as the Romans. And they're still finding, they're excavating, you know, old Roman encampments and finding Black African nobility women. And they are doing documentaries on it. I've been in a few. So it's become quite a well-known issue now. Although there's still a great sense of many British people wanting not to understand or believe that past.

I wanted to make people see … that these people are walking the same streets, we're living in the same neighborhoods. And I wanted to make it a living, breathing history.

Plain Jane

So I suppose, as you say, this was almost 25 years ago, that Black London came out. You've mentioned in the BBC series that you did, Britain's Black Past, you mentioned that it's a detective job … finding these stories. How have you managed to find the stories that you found? And what was it like putting that into an audio series?

Gretchen Gerzina

That was wonderful. And of course, it became a book, which was published when all the new research came out last year. So I was able to update a lot of the things … I've got to say - you're in radio - these producers … who have these independent companies and do the productions for BBC, they're incredible researchers. They sometimes find people that I hadn't been able to find, because we academics think in a very different kind of way than radio and television producers, who are out there finding people. So … I knew a lot of the people and we went to some of the places - but they were able to find some people I didn't know about. And then there were incredible stories … I think I was supposed to originally spend six months doing it. And then I was about to change jobs. And I only had one month. So I think I traveled all over Britain in one month doing the entire series. I would wake up in London and get on the train to Glasgow, spend the afternoon in Glasgow, come back to London. The next day, I go to Bristol, you know, kind of went on and on like that.

Plain Jane

That [sounds like] a really fun part of it.

Gretchen Gerzina

Yeah, it was very tough. … Going to some of these places to really stand in the houses or on the shore. … But it was quite an adventure, to unearth some of these stories. And to just see how, for many people, these stories still last. People still really care.

Plain Jane

What stories have fascinated you? What have [written about] so many individual stories that are wonderful to hear. But what have you found most surprising and exciting to discover?

Gretchen Gerzina

There's one - maybe it's one of the ones you're gonna ask about - which is Nathaniel Wells. And I resisted using that story. But they really pushed me because I hadn't really known it before. Nathaniel Wells was the son of a slave owner. He was mixed race. So he was the son of a [enslaved woman] and a slave owner. The owner … had daughters, but no legitimate sons. … He left this money to this mixed-race son ... He sent him off to England to be educated, as many slave owners did with their mixed-race children. And he went to boarding school and he studied. And then he died when Nathaniel was only 20 or 21, when he became the heir. He spent a lot of money. He was a young guy, and he moved to Wales to Chepstow. And he used the money to buy this enormous place.

He built this incredible house. He had acres upon acres of this scenic land that was so gorgeous, that it became a kind of pleasure ground. And people would come - there was an open day - and they could come and walk through the parks and all of the mountains, and it was quite something. But he made his money. His money came from the slave plantation. And in fact, his mother owned slaves, his mother, who had been herself enslaved, and I was very reluctant to tell the story of a - essentially a Black or mixed-race - slave owner living in Britain. He married a succession of wealth, to white women … and his house is a ruin now. But he became the first Black sheriff in Britain. He had this enormous wealth. He didn't die with a lot of money. But his story was one I never expected to find.

The one in my heart is always Ignatius Sancho, who's now been a play and everything.

Plain Jane

Why is he the one in your heart?

Gretchen Gerzina

Well, because he was so amusing and so serious at the same time.

He was brought as an enslaved child. He managed to get away, he was taken in by the Montague family, finally, away from these “three witches,” I think people call them now, who had owned him, didn't want him to read.

So they took him in, he was educated. And he became a butler in their house for many, many years. And then he was a little on the heavy side, and then finally couldn't continue to do all his work. So they gave him a pension, and some money. And he moved to London.

And he … set up a shop in Westminster, right near the heart of everything of the movers and shakers of British aristocracy and politics. And people would come into his shop. He married a Black woman, which was unusual at the time. And he wrote these letters, and he knew everybody. I mean, they would come in and talk to him. Laurence Sterne. He wrote to Laurence Sterne and [said], “If you're writing Tristram Shandy, please say something about slavery in there.” And he did. He had his portrait painted by Gainsborough. And it's quite a beautiful portrait. It's unfortunately in Canada - the British realize they made a mistake and are trying to get it back. I don't think they're going to get it. …

And he was just somebody that people were so fascinated with - all of his letters have been published, his son arranged that they got published after he died. And he’s still considered just a huge character. I mean, he … saw the Gordon riots and wrote about them in his letters. He knew people. And he was kind of the face of 18th century Britain in some ways, even though he's a Black man. He was also the first Black man ever to vote in England.

Plain Jane

So many of these people were close to influential people and so therefore having an influence. As you point out, they're the easier ones [to discover], and the people who are able to write their own lives are easier to unearth and to find. But so many of the experiences of Black residents in London during this time were below stairs or quietly or really by necessity a lot of the time having to be under the radar. ...

Gretchen Gerzina

It's hard because … for instance, the British census doesn't list race. When I first published Black London, some reviewers said that I should have gone to all the rent rolls and seen who was Black. But the rent rolls don't necessarily indicate race. It's really hard to find. But the same thing happens in America. … When my book Mr. And Mrs. Prince came out about 10 years ago - it was about two formerly enslaved people who lived in New England in the 18th century. It was a long time ago. And all the stories that had been written about them were written about other people, most of whom got the facts wrong. They claimed that their ancestor had freed them or things like that, that proved not to be true. I had a publisher ask me if I had a photograph of them. And I said, “There was no photography in the 18th century, you know, what do you expect?”

And… in general, you don't have your portrait painted, you don't have a journal, you're too busy getting on in life … If you're literate, you don't necessarily sit down and pen your memoirs, you know. You're just trying to get going. But on the other hand, there were people like Francis Barber, who was the servant of Samuel Johnson, and became his literary executor and heir at the end. And that was much disputed. And people were not very happy about that. So those kinds of people who were educated and were lucky enough to be known [we can learn about]. I actually think that the people who are finding out the most now are people you don't expect - genealogists who are starting to trace back family histories. A lot of white genealogists in Britain, they're finding that they have Black ancestors, and they didn't realize it.

Plain Jane

I’m a big fan of “Finding Your Roots” with Henry Louis Gates, Jr. It seems like he ends every episode saying, “See how we're all connected? More than we thought we were?” … So yes, I hear you, that's really fascinating - that so many disciplines are sort of reevaluating and re-seeing, looking again, revisioning, all of this history. You’re reminding me, when you talk about no photography from 18th century Britain, you're reminding me that not only are you and scholars like you having to honor these unseen histories, but you're actually having to re-tell stories where there's been a campaign of basically very racist imagery. You write about the constant, reinforcing sexualization of Black women from these times; but then also the pro-slavery imagery and campaigns that were put out there. Even the sentimentality. You say that there's sort of two versions that even those that were anti-slavery at the time, were sort of overly sentimentalized versions, like we think of Harriet Beecher Stowe. And, you know, doing a lot of good work, I suppose, and having an influence; but yet, we need to revision those stories as well. And you mentioned that you're just looking for the real people. They're real people in real places. So [you are] … having to, as you say, repaint these people?

Gretchen Gerzina

Well, I mean, just remember it's all worked very differently in America, and in Paris. And the way that it's memorialized or remembered is very, very different. There were certainly Black people in Britain from hundreds and hundreds of years. But there was not slavery on their soil in the same way that it was here. So they were able to sexualize women by looking at the Jamaican plantations and what happens there with a lot of rape and a lot of punishments. But this is the country, Britain is the countries, I should say, where Black minstrelsy was a television show until the 1970s. Blackface minstrelsy was not only on television, but it was in all the private homes. But at the same time, in the 19th century Uncle Tom's Cabin was the biggest thing going. People loved it, it really spoke to them. So there was Uncle Tom wallpaper. There [were] Topsy dolls. So you would go into a child's nursery and there could be wallpaper and dolls.

So that sense that America was terrible, and “Look at us, we're so great. We abolished slavery before you did,” takes away the fact that for the most part, the British actually supported the American South in the Civil War. Because their cotton came from there that fueled their textile mills in the north of Britain. They didn't have the same kind of racism, it worked a little differently, but it certainly existed. But there were lots of people who were just living among them who were not necessarily known. They weren't necessarily in a book, and they were just sort of living their lives. And that's what I'm trying to write about now.

But also I just really want to have a shout out to some people who are working on these things now. Miranda Kaufmann's book, Black Tutors, really sparked a huge response. … It became a huge bestseller in England. And there was a lot of pushback when people said there were no Black tutors. And she would show them the images of the people, and then all the documentation, and they didn't want to believe it. I belong within a group that she started, that is looking into Black people in British portraiture, and trying to identify who those people were. And so far, the list has over 300 British paintings that have Black people in them - they're most often a small boy servant or something, but not always. And they're scattered all over. They're in private homes. They're in museums.

But there were lots of people who were just living among them who were not necessarily known. They weren't necessarily in a book, and they were just sort of living their lives. And that's what I'm trying to write about now.

So there is a kind of visual reality to all of this, where you can see the people and you can understand a bit about their lives. And so people are going into the records trying to find out, who were these people? Were they borrowed sometimes, some painter would say, “Oh, you know, he's got a Black servant, let's put him in the picture and bring him over to a bigger house for a while.” So you know, trying to track them down is difficult. But there's just more and more evidence of this ongoing presence.

Plain Jane

You point out now in in your works the way these stories have been played, have been part of popular culture through the ages. And I guess our culture - various cultures - have worked out the stories, have worked out some of these things, either effectively or ineffectively, on the stage. And so that brings me to where much of your research deals with - the Regency era, which happens to be where so many contemporary cultural retellings, fan fiction, and romance is taking place. And then of course, we've got Bridgerton. So let me just start with a general question. We're talking about what people typically miss, but how are you experiencing some of these cultural inventions?

Gretchen Gerzina

Yeah, you know, I'm enjoying the heck out of this stuff. Just like a lot of [us].

Sanditon, I can let go. It was, I felt, a travesty. It kept some of the book, but it actually just took things in a direction that I found very difficult. So, for example, in Sanditon, the Jane Austen novel - the fragment because it's incomplete - the heiress from the West Indies is Miss Lambe … She is not necessarily identifiably Black. They know she's mixed race. In the series, they made her a very dark-skinned woman to point out that she in fact was a Black woman. They wanted to make that visual sense very strong for people like “Oh, we're dealing with a Black woman here.” Whereas I think in Austen it was more subtle and probably more accurate about how somebody like her would have been seen.

But Bridgerton just went over the top, and I just thought it was fabulous. Because we do know that Queen Charlotte probably had some mixed-race background. She was the wife of King George III. So she's presented as a mixed-race or dark woman … But then by just making everybody in it, you know, it was like saying, “Okay, what if we recognize that all these people were there? And assuming that they could have made their way into the aristocracy, how would this world have looked?” And I think the visual treat of it all is just really great. And we all know that that is not how Regency England looked. But we can say, “You know what? I would like to see what this looks like. If this could have been true, what would it have looked like?” And of course, it's just like a visual feast anyway. It's not just the racial stuff. It's the clothes and the sets.

Plain Jane

Tell us more, Professor Gerzina, about Queen Charlotte. You did an entire Zoom talk event with JASNA, the Jane Austen Society of North America, about these questions, and this sort of casting and Black Britain and its history. And there were hundreds of people on the Zoom. But you talked about Queen Charlotte, and the chat room just went crazy. … So it was very, very lively. So anyway, all of that to say - tell us about Queen Charlotte?

Gretchen Gerzina

She had … Portuguese family so that there were a lot of that movement between North Africa, the kind of what we would think of as North Africa today. But she probably had some ancestry through her Portuguese ancestors who might have been Black. When I was doing some research on Black people who left America and moved to Canada after the Revolutionary War, those who had become the British patriots, the Black ones, a lot of them went to Canada. So I was in Nova Scotia at a center there on Black history in the province. And I noticed they had - I think it was a picture of Queen Charlotte on the wall - and I said, “Oh, what do you think of that? Do you think she was part Black?” And he said that Princess Anne had come to visit many years before and had seen the portrait and was asked about it. And she said, “Well, everybody in the royal family knows she was Black.” So that means to me Meghan Markle wasn't the first. So there's some history there. It can't be necessarily proven, but it's pretty well seen as probably true that she had some Black ancestry, and her portraits do seem to indicate that as well.

But you know, the other one I really like is David Copperfield. And what you have to do in this - the same as in fiction - is you have to create a world that you will believe. You may not like all the characters, but you have to create a vision of a world that you are saying, “Okay, I'm, I'm willing to go into this world with you.” And see and believe. It's the willing suspension of disbelief, and I'm willing to do that. Do they create a world that I can believe in Bridgerton? We know it's fantasy, and fun, with some historical elements. And yes, I'm willing to throw myself into that world.

Plain Jane

I was a graduate student at UCL in London, during 1994 and 1995, and everybody was reading Cultural Imperialism. I literally saw people reading it on the tube in London. And I was falling in love with someone who was an Arab-English person with the name Saidi - close to Edward Said’s name. So I was as a grad student in literature and also wanting to dive into our views and our histories and how race plays into that. These conversations are still going. Edward Said even writes about Jane Austen. And he writes about Mansfield Park, and he writes - really similar to you writing at the same time - we need to investigate the unseen in these stories, tell the unseen stories, which is so much what you're doing, as well. So my question is - almost going on 25 years, are we getting any better at this?

Gretchen Gerzina

Well, you know, there's more being written and more being published all the time. David Olusoga’s books. And all of his television programs in England are very well known. He's quite the face of Black British history and studies now. Others have been writing about it for decades. But I think what's interesting is that there's still a kind of resistance to it, to believing it. There are several things going on. One is ... the report the National Trust put out recently, which ... hired some academics and some others to take a look at the colonial and imperial and slave connections between some of the National Trust houses. And I think they listed 93 houses in the National Trust that have some kind of connection. That wasn't to say that they were houses where there was plantation slavery or anything, but a lot of it had to do with the fact that the money that was earned either out of the slave trade, or out of imperialism, or out of colonialism. [It] funded and help build, and perpetuate those houses. A lot of the money that was earned came from, originally, from the slave trade and slavery, and all of those absentee slave owners who had plantations in the West Indies. But also, from the fact that when they, when slavery ended in the West Indies in 1807, that they decided to compensate the slave owners for the loss of the enslaved people who had lived on those plantations.

The enslaved people were not compensated, while the slave owners were. And a wonderful book and study done by Nicholas Draper, about the legacy of all of this showed how all of that money that was made from that compensation - built these houses. It funded the philanthropy; huge swaths of London were built based on that money. And all around the country. So they wanted to just say, “Hey, if you're going to come to one of these houses, this is great. You can look at it, you can see it, you can appreciate the beauty of it. You can see how the generations of owners contributed to the culture and the landscape and all of that. But in fact, you should recognize that the money came from colonialism. And also from imperialism.”

You know, the houses were filled with porcelain from China. They were built on land that used to be tenanted, but pushed the tenants off and made a beautiful landscape that made it look like it had always been there. And they had built these houses based on that money. When that report came out, the backlash was quite strong. People did not want to hear about this. They thought, “Why do we fund a National Trust, and it spends its money on being woke?”

Plain Jane

Interesting. They don't see it as factual. They don't see it as history. They see it as politics happening.

Gretchen Gerzina

Yes, they do. And there's also some work being done now on updating the curriculum in schools. So some more of this is being learned at a younger age.

Plain Jane

So when you say in 1993, and you've been doing this ever since, among many other things that you're reconstructing, you don't even just mean that figuratively. I mean, your writing takes us down the streets. And really paints a visual picture ...and I would add to that the landscapes of the houses. Also sugar and so much of the economic foundations are part of what I think Edward Said was calling the interplay. … You you paint a picture of, you know, Elizabethan England and … Regency England then as well, and then even Victorian Britain as being a very cruel and violent place. And I think that in many ways, our PBS adaptations [etc] really do [whitewash] these histories in so many ways. You also point out the cruelty, the disease. But what I want to say, besides the cruelty, the disease, and just the ignorance that was rampant in these times, that we tend to forget about - probably, thanks to our screen adaptations - it was there. You found a community of Black residents in London during these times - not just individual people who were famous; they were portrayed on the stage; they were recounted in stories; and many of them were musicians, writers, very fascinating individuals - but also a community. And that was you've talked about how difficult that was to unearth. Can you talk about how you uncovered this community and the difficulty of doing that?

Gretchen Gerzina

A lot of that came from people who had been researching this for quite a long time. In terms of community, there are people who've been doing tons of research since my book came out. And they have been finding people and they've been finding communities. We can't be sure how much of a community there was. But we do know that there were communities - people lived in certain places and certain areas, they were part of the fabric of the kind of working class. There were people that we call the Sons of Africa. Some people have questioned whether there were as many and met as frequently as was thought … But we do know that they were there.

“Hey, if you're going to come to one of these houses, this is great. You can look at it, you can see it, you can appreciate the beauty of it. You can see how the generations of owners contributed to the culture and the landscape and all of that. But in fact, you should recognize that the money came from colonialism. And also from imperialism.”

And it was interesting to just think of the fact that in all of these grand houses that had Black servants, that those servants in the households, they socialized with each other. Those servants were meeting in the kitchen. Those servants were talking. And those servants were marrying the white servants, because they were mostly Black men.

And then you get a sense of just this kind of other world where if Samuel Johnson is having dinner with Sir Joshua Reynolds, or with the great actors of the period, that their Black servants are probably hanging out, talking to each other. So there was a kind of network of people, definitely, who were living [among] them. And then, of course, after the Revolutionary War in America, when so many Black people had been convinced to fight for the British in exchange for their freedom. A lot of them ended up in Britain, that had been part of the promise. And so they came over in their hundreds.

Plain Jane

That's fascinating - I think that you pointed out that something like 20 percent, of the soldiers fighting on both sides in the Revolutionary War with America were Black soldiers. They came back to England. And then you also pointed out they were not allowed, they were actually banned from learning crafts, learning trades ....?

Gretchen Gerzina

I'm not sure that they so much were banned from learning trades; they just found it difficult to find work. And also if, if they were poor, it's not so easy to move around in England at that time. I mean, physically, it's difficult. But also, it's often difficult to find work. And if you, Heaven forbid, get sick and die, you can't necessarily be buried where you're living because you're not officially part of that parish. So it's a very different kind of system than we might [envision].

And so a lot of people who worked on the British side, and obviously on the American side, in the Revolutionary War, were not just soldiers but they were doing other things: They were guides, they were helping to lead them through different terrain; they were washing clothes, they were cooking. They were following them and giving them advice.And then they also did fight. So, yes, they worked in a variety of ways and the British said, “Hey, come on our side and we'll give you your freedom and we'll give you a pension.” And then, lo and behold, the British lost then, and they came.

Plain Jane

Okay. So: Dido Belle and Mansfield Park - basically thoughts on that? There's also the book The Woman of Colour and there's this experience of Francis Barber and some of the others that you've mentioned. But … what are your thoughts on Mansfield Park and is it possible that Jane Austen knew the story of Dido Belle?

Gretchen Gerzina

It's possible. I have to think about the timing of it all. So Dido Elizabeth Belle of course, has nothing to do with Mansfield Park, although her great uncle who raised her was Lord Mansfield, who made a famous court decision that a Black person could not be returned to slavery in Jamaica. And that was taken by many people to say that slavery was no longer legal in England, and people ran away and said, “Hallelujah.” But in fact, that's not what the decision was.

He also presided over the case of the Zhong [ship], where a slave ship had thrown over a huge number of people ... in order to collect the insurance. And he came down hard on that case. So Dido Elizabeth Belle was raised by him .. but a lot of research has been done since the film Belle was made. And a lot of that film took a lot of liberties with it. So Dido was mixed-race, and her mother was - [but] Dido was not - born into slavery. And that was a misconception. Her mother actually came and lived in England, near her, with her, for some time. And then went back to Pensacola, where she had been living in [an] old property. Dido was given some money, and so she was able to marry. But she didn't marry an abolitionist, like in the film. She married a man who'd been a steward to an important French family. And so that was still a high-up position, but it was not the big raging lawyer abolitionist [as in the film].

… And I think the biggest thing about it was that her portrait was just a double portrait of herself, and of their cousin. It became the cover of my Black London book - and was later re-used by The Woman of Colour. So there's a lot of interpreting this portrait that people try to do.

So I've spent a lot of time trying to track down the true story, to use the research of these other people who have done such a good job.

Plain Jane

What would you like people to keep in mind as they're watching and reading Regency era histories and romance?

Just realize there are real people behind some of this. We know now that Jane Austen was likely an abolitionist, although she didn't write political things in her novels. We know that in Mansfield Park there are mentions of - and we know that the money came from - slavery. And so there was some reference to sugar and some other things in there. So we know that she's aware of it. But she doesn't make it front and center, because that's not what she does as a novelist. But I think it's really good for people who want to read these books - [to know] that there was a more racially diverse society than people realized. And that there were Black people there. And that in the places where she went and lived - because she lived in a number of places, she had to move around a lot - that she would have seen people like this.

And so it's really good to remember that this was a very different world and people have now accepted it. And I think to understand and accept that, it makes it more interesting. It doesn't diminish it at all.

——-

Thank you for listening, reading and being with us, friends.

Let us know your thoughts!

Have you watched the increasingly diverse casts making up Regency and 19th century British stories like Bridgerton, A Personal History of David Copperfield, and Sanditon? What would you like to see more of in these retellings and screen adaptations? Want to know more about Queen Charlotte? Write us at AustenConnection@gmail.com.

If you like this conversation, feel free to share it!

And if you’d like to read more about Black life in Britain in the 18th and 19th centuries, here are some of the people and projects that Gretchen Gerzina mentioned during this conversation - enjoy!

Gretchen Gerzina’s website: https://gretchengerzina.com//

BBC program on Britain’s Black Past:- https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b07wpf5v

See: National Trust research into the connection to the slave trade in its great houses: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/features/addressing-the-histories-of-slavery-and-colonialism-at-the-national-trust

The report: https://nt.global.ssl.fastly.net/documents/colionialism-and-historic-slavery-report.pdf

All things Georgian - Gretchen recommends in interview: https://georgianera.wordpress.com/

David Olusoga: https://www.manchester.ac.uk/discover/magazine/features/david-olusoga/

Dido Belle as Fanny Price: http://jasna.org/publications-2/essay-contest-winning-entries/2017/a-biracial-fanny-price/

Peter Fryer’s Staying Power: https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745338309/staying-power/

Mirands Kaufmann’s Black Tudors: http://www.mirandakaufmann.com/black-tudors.html

Get these and all our Austen Connection conversations delivered to your inbox, when you subscribe - it’s free!

The Podcast - Episode 4: Black British Life in the Regency and Beyond